TRAPPED IN URBASA

For some years now, the convention poster has become a small testament to our love of history. It’s something we approach with care and dedication, and for which we couldn’t do anything but enlist the best possible illustrators. Both Iván Cáceres and Nils Johansson patiently endured our lengthy discussions about which era to depict, how to do it, what to convey, framing, uniforms, color palettes… Their patience and talent gifted us with some marvelous illustrations, the kind some hermit from Burgos might use to decorate the walls of their game cave.

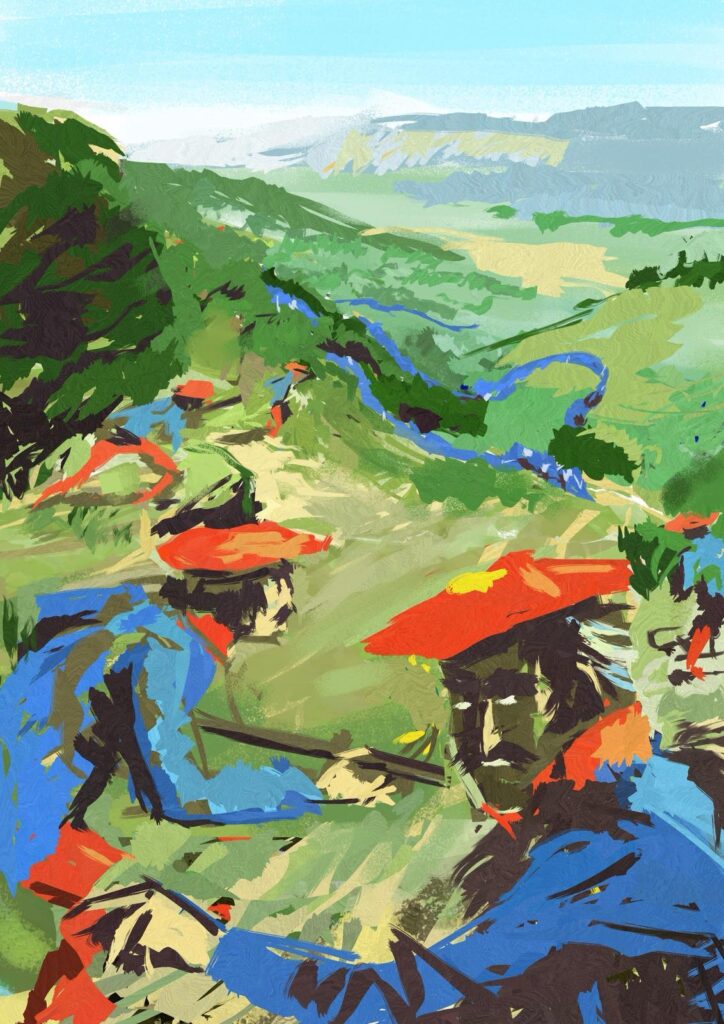

In the latest edition, however, we have the brushes of Josean Morlesín: framed in the “Guides of Álava”, doctor and professor in Fine Arts by the UPV, Vitoria “Bunkero” and fearsome general of Dwarfs, Josean also illustrates film posters for his friend Paul Urkijo, designs 3D models like a modern Phidias and, between dancing with the muses and conversation with Apollo, devours good hours in the park fulfilling the fateful sentence in which we are mired lately.

Last year, we explored the Duero frontier, a tribute to all those regions where, at some point in history, the dynamics of power vacuums, raids and incursions, hard-nosed pioneers, protected settlements, and mercenary adventurers have been replicated. During its creation, we exchanged countless opinions, viewpoints, and ideas. The different versions gradually brought us closer to the final one, and it was the endorsement of Eduardo Kavanagh, head of Ancient and Medieval at Desperta Ferro, that ultimately reassured us.

This year has been no different, although it’s true that the initial brainstorming session was considerably shorter: no matter how much the Chinese say that next year will be the “Year of the Horse,” we’re absolutely certain that, at least here, 2026 will be the “Year of the Carlist.” An Impossible War was finally published in the autumn of 2025, a joy comparable only to that of the Greeks who shouted “Thalassa” two millennia ago, after a very long publishing journey.

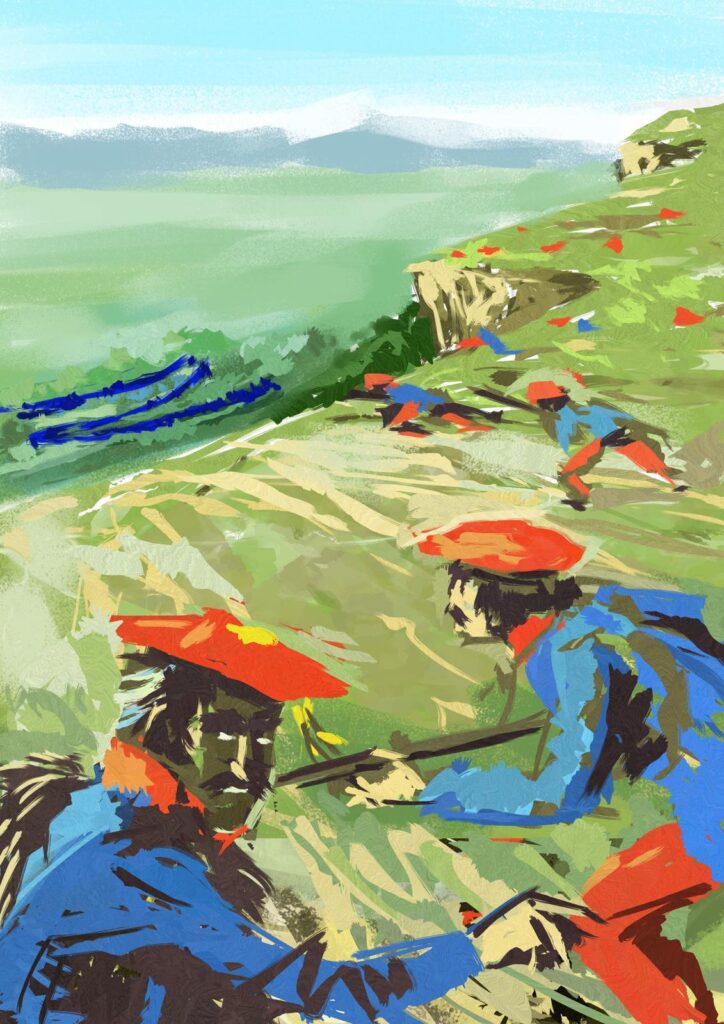

Very well, berets then, but… when and where? In my opinion, the Carlist heartland has very precise coordinates: Estella, its capital of wealth, and especially the mountain range that protects it: Opacua, Urbasa, and Andía. Anyone who has traveled the highway between Vitoria and Pamplona will have noticed, to the south, the impressive longitudinal cliff that stretches for dozens of kilometers, with Mount San Román as a brutal bastion that dominates the entire U-shaped valley of La Barranca, also known as Sakana. With Aizkorri-Aratz and Aralar to the north, covering the almost 100 km that separate the two capitals must have been, for the liberal columns, the worst imaginable nightmare: aliens in red berets and predators with burnside sideburns were lying in ambush.

With the location determined, the only question was when. Turning to history, David and I had no doubt: the Battle of Artaza. On April 22, 1835, Zumalacárregui, with little more than 5,000 men, dealt a crushing defeat to Gerónimo Valdés’s column of 22,000 liberals at Las Améscoas. The trap had been patiently and cunningly laid since the Cristinos left Vitoria three days earlier. The moment depicted on the poster is from the 20th, when, after spending the night in Salvatierra de Álava, the column decided to cross the Olazagutía pass into the “green desert” of Urbía.

The Carlist lookouts, therefore, are positioned at the top of the pass. The crags in front form the Egino mountain range, with the Aratz and Aizkorri massifs in the background. To the left, the Álava Plains open up, while to the right, the menacing shape of La Barranca gorge comes into view. The old Olazagutía pass, with its unmistakable horseshoe bends, thus becomes a serpentine blue snake advancing towards its doom. As an expert on the area, I cannot express how impressed I was by Josean’s perfect depiction of it with just a few strokes and a few shades of color.

Urbasa, therefore, is a karst mountain range where finding water is difficult. Let alone food. Any satellite image will confirm this: without villages and with barely a couple of roads crossing it, the mountain range is a place of extraordinary beauty but uninhabited by humans even in the 21st century. Just a few sheep graze on its slopes and in its forests, the ones responsible for the famous Idiazabal cheese. In April 1835, however, Zumalacárregui had taken care to deprive the Isabeline forces of any supplies.

And so they climbed up, unaware that the trap was closing. The other geological feature of the place is that the plateau is surrounded by a continuous rock wall, broken only at specific points such as the Olazagutía pass itself or, our future protagonist, the Artaza pass. For when the liberals tried to descend from those desolate lands, they found that Uncle Tomás had gathered his meager troops to block their path.

The punishment was severe, and only when their ammunition ran out were the remaining liberals able to return to the valley. The consequences of the action were immediate: the Cristinos retreated to the garrisons of Vitoria, Logroño, and Pamplona, while the Carlists began to advance into the Basque Provinces to prolong their own “Impossible War.”

Versions

Throughout the process, we were constrained by a compromise between historical fact, natural beauty, and artistic composition. The initial sketches depicted impressive cliffs, realistic in terms of the terrain’s geology, but their sheer size made them impractical for the ambush. Furthermore, the most rugged part of the mountain range is the northern slope, not the southern, precisely where most of the access passes, such as the Artaza pass, are located.

The solution was audacious: not to depict Artaza’s actual action, but rather the beginning of the ambush two days earlier. The exact moment when Zumalacárregui realized that Valdés wasn’t just making a show of force in the valleys, but was actually seeking a confrontation. It was precisely then that “The Wolf of the Améscoas” sent messengers to gather his small force in the mountains and cut off their descent.

The different versions followed, taking into account the terrain, the time of composition, the light, the position of the sun, the colors of the vegetation in April… As for the always difficult subject of Carlist uniforms, the solution was clear: to turn to our captain of the “Guides of Álava,” Don Raúl Mendo Herrán. His record as a wargamer, miniature painter, historical reenactor, and renowned expert on our historical and military heritage makes him the person to consult with any doubts. He recommended restraint with the red berets, as it seemed that only a few officers and very few regiments wore them, with blue berets being more common.

A special mention should be made of an idea that we abandoned early on, but for which a sketch exists. Josean, imbued with the Romanticism of the time, discovered a real passage in which, the night before the battle, the memoirs of two officers from opposing sides recount the bivouac that takes place when both forces are within two rifle shots of each other: the enormous liberal column, located on a high point outside Contrasta, is observed by the lancer captain Henningsen, his gaze meeting that of Fernando Fernández de Cordova.

The final poster is a highly narrative composition with a rich depth, in which, although there is no direct action, one can sense the preparation of a complex ambush that would punish the liberals two days later. As Paco Ronco aptly pointed out: “Ambushes are set to prevent the enemy from escaping an uncomfortable position.” The Urbasa mountain range, as it had been for the French, was that difficult place. It was also a refuge for the legendary Carlist light infantry.

Tribute I want to end this article by dedicating this poster, with Josean’s permission, to Ekhi Arroyo Fernández de Leceta, originally from Ullíbarri-Arana, a town next to Las Améscoas. Since childhood, we explored those mountains, sleeping in tents and taking refuge by the fire in his grandparents’ house to taste the best potatoes in the world. A year ago, precisely on the crags in the background of the drawing, what was mortal in him left us. May the gaze of that officer in the foreground serve to remind us of the immense fighter he was. We remember you forever.